Volume II

Oral History

of Service

Second Tour of Duty

1943-1945

George J. Baird

|

|

-

“There is a mysterious cycle in human events.

To some generations much is given. Of other generations much is expected.

This generation has a rendezvous with destiny.” Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- 1936

-

We came back to the United States under the Golden

Gate Bridge into San Francisco where we incidentally had departed from

on our original trip out. We went from there back down to San Diego

to Camp Elliot, a regular Marine base for processing. We were to

stay in quarantine for 3 days and not be allowed to go on liberty or anything,

but as soon as I arrived there I had somehow gotten in touch with my friend

Bernard Young and he and I went into town together. He was by then

a Lieutenant. He got me a pass and I was so anxious to get home that

the trains took four days and as we got on the train and then got closer

to Ohio it looked like we were taking an awful roundabout way from Chicago

to Cleveland. There was a stop that the train crew told me that they

were making where there was a train that went directly into Cleveland.

It would get there hours before we would on this train. So I got

off the train in Crestline and lo and behold, the trains no longer were

running. I asked somebody what the best thing was to do, and

was told there was no direct way, buses or anything else to Cleveland but

that I could get a bus to Akron and take a bus from there to Cleveland.

So that’s what I decided to do. I got into Akron and was standing

in the bus station waiting for my bus when a little old lady came up to

me and said “Bus driver, what time does the bus leave?” So my Marine

Corps uniform wasn’t all that well known in Akron, evidently.

The Akron Bus Terminal/Ohio Edison Building

– Christmas 1935

“Bus Driver? When time does the bus

leave?”

-

I was to come into Cleveland and then find I could

get off the bus at the corner of Broadview (Rd.) and Pearl (Rd.), rather

than going all the way downtown. So I very cheerfully hopped off

and went over to stand in front of the Broadview Theatre to wait for the

bus to come up Pearl Road to go home. By this time, the train I had

started out on had long since been in Cleveland and Rita and her folks

had been downtown waiting for me, and of course I wasn’t on the train.

So they were on their way home and as luck would have it, they passed Broadview

and Pearl while I was standing there waiting for my streetcar.

-

-

Cleveland Streetcar (1952 picture)

“I was very glad to be home.”

-

We had our reunion in the car at the corner of

the street, rather than any place we were supposed to. But I was

very glad to be home.

-

While things had been somewhat uncertain between

your mother and I when I first went overseas, we became much closer on

this 30-day furlough and were to soon begin talking about getting married,

and in November, did just that.

-

Wedding Day Picture (Personal Archive)

“We were talking about getting married…..and

did just that.”

-

This was also the last time I saw Frank

Glover. He was still home, although he was reporting back to Shepherd

Field in Texas for his flight training. He and I spent several days

together visiting old spots and stuff like that.

-

At the end of the 30 days, we separated again

and I went back to New River, NC for reassignment and was sent by truck

up to Cherry Point, NC, which was the Marine Corps air base on the East

Coast.

-

Cherry Point Air Station

Construction of the 8,000 acre Marine Corps

AirField at Cherry Point began in late summer 1941. The December

attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese lent urgency to completion of the

complex, located in Craven County between New Bern and Morehead City.

On May 20,1942, the facility was commissioned Cunningham Field, named in

honor of the Marine Corps’ first aviator. The complete facility was

later renamed Marine Corps Air Station, Cherry Point, after a local post

office situated among cherry trees. Cherry Point’s primary World

War 2 mission was to train units and individual Marines for service in

the Pacific Theater.

-

|

-

I was to become part of the 3rd Marine Airwing,

and a group called Marine Airgroup 33, and was assigned to their headquarters

squadron. (See Appendix 1) My first job, however, was picking up trash

in the yard around the barracks. I was a PFC by that time, and in

fact had become a PFC while we were at Pearl Harbor. Getting that

promotion in days when it was very hard to get any such thing at an established

outfit like the 3rd Defense (Battalion).

-

One of the officers who later was to become pretty

much a friend, as well as my immediate superior officer, was a Capt. Cannon.

He evidently saw me out there with my Guadalcanal Canal patch on my sleeve,

picking up the rubbish with my stick with a nail on the end of it, and

raised holy hell.

-

Shoulder Flash for the First Marine Division

on Guadalcanal

-

I suddenly found myself assigned to the

post office, and had an assistant. In the next two or three weeks

I was promoted to Corporal and Sergeant, almost faster than they could

write up the papers. So, because of problems in the leadership of

the crew in this group post office, I was made the Navy postmaster for

it, which I did for the rest of the war. I was in charge of the post

office with anywhere from three to five men working under me. We

handled all the mail for the group.

-

In time, as we decided to get married, we tried

to set a date and I tried to get a furlough, although since I had just

had the 30-day leave it posed quite a problem. Our Capt. Dickey was

kind of a curmudgeon, and he said he didn’t care whether I wanted to get

married or not - I just didn’t have the leave coming to me. So we

finally agreed that we would get married, but in Baltimore which was a

fairly easy place for me to get to on a weekend, or three-day pass.

The idea was that Rita and her family and Nettie would come down and we’d

be married in Baltimore. We had to go through the usual red tape

that the Catholic church involved at that time getting permission and going

through my own Catholic chaplain at the base who wanted to know what the

hell I thought I was doing... not using those words, but expressing very

firmly that he thought I was in a big hurry. Why couldn’t I wait until

I got home? Why did I have to go to Baltimore? Why couldn’t I go to my

own parish? When I told him I wasn’t a Catholic, that just made it worse.

He didn’t want to see a Protestant marrying a Catholic at all, but eventually

I got permission.

-

I believe the afternoon that I was leaving on

my 3-day pass; Capt. Dickey relented and made it a week. It was too late

to change plans, so we still ended up in Baltimore getting married over

the Thanksgiving weekend. By having the extra days, we were able

to go to New York for a short honeymoon. We could have gotten back

to Cleveland and been married. We never got wedding presents because

everybody said they would wait until we got home, and then of course, people

forgot all about it. But we were very pleased. Fran and Betty

were in New York at that time. Fran was stationed close by, so we

were able to join them for a short time.

-

-

-

Wartime Wedding- November26, 1943

(Personal Archive)

“Then it was back to the base and your mother

went home.”

-

We quickly found a place to stay in a one-room

situation in Morehead City, which is a very nice town where we often talk

about how great the food was. Your mother eventually got a job at

the base at Cherry Point and so that was the beginning of our established

married life. I ended up at a place called Bogue Field, which was

a subsidiary base to Cherry Point, so we weren’t at the main base.

I did make trips every day to Cherry Point, hauling mail and personnel

back to Bogue Field. The personnel situation was kind of a sad thing

because these people I brought back were to replace people who were killed

in training, flying their airplanes, and who quite often would (practice)

dive bombing and dive straight into the water. We had a lot more

casualties there then we would have in the Pacific. But, after all,

these were first-time flyers and there was no other way to learn but to

get up there and fly.

-

The post office obviously gave me a lot of advantages

over being a routine Marine sergeant or otherwise, because I had my own

tent and my own office and was pretty much in control of the time.

Prior to the time we set up housekeeping, Christmas rolled around and while

it took several days to get from North Carolina to Cleveland, I decided

I was going to go home for Christmas come hell or high water. So

I got a 3-day pass, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, and got my guys in the

post office all set up and left on Thursday and made it up to the Rocky

Mount railroad station which was the jumping off place to come north through

Washington DC. To my horror, there was a lineup of what looked like

thousands of guys waiting to get on the train. I went up to one of

the Marine MPs, and talked to him about it. As it happened, there

was a guy who knew of my outfit and he said he was sure there wouldn’t

be more than a 1/2 dozen guys getting on the train. He thought the

train would already be full when it got there. So he asked me to

stand by and sure enough, when the train pulled in it was absolutely packed,

but the MP got me on. In order to get from the platform where you

got on the train to any place in one of the cars, you actually had to walk

on the backs of the seats because there were guys sitting on their suitcases

in the aisles. But everybody helped you along until you found a new

place to squat somewhere in the aisle. This would never have been

permitted in peacetime. The place was like a load of sardines going

to market.

-

To make a long story short, I did get home.

I did have 12 hours total until the time I took another train and headed

back. I was late going back, and kept worrying for fear that someone

would check my papers and ended up sitting with an officer on the train

and chatting with him most of the way and had no problems at all.

I got back to camp a day late and didn’t have to report to anybody.

-

Once we found a place to live down there, we were

very happy about the whole thing because obviously I was unfit for actual

combat duty anymore, which was one reason, supposedly, that I was running

this post office. There was no great chance of my having to go overseas

again. Unfortunately, that changed pretty rapidly, and after the

stay at Cherry Point, I was to be put on a train again, heading for the

West Coast. So we said our good-byes. (See Appendix 2)

-

This train was an old fashioned sort of thing,

sort of semi-cattle car, but we were on our way. We went through

Tennessee on the way and ended up marching down Peachtree Street in Atlanta,

GA. We were in town, (we had gone and eaten in a restaurant) and we were

marching back to the train. When we got on the train, we found out

that new orders had come in and we were not going to California... we were

going to Texas. So we ended up at Eagle Mountain Lake, Texas which

was somewhere between Fort Worth and the same Shepherd Field where Glover

had had his training. The very first day we got there we were told

if we had a proper uniform we could go into Ft. Worth on liberty, and that

there was a bus that stopped at the gate. By this time, being somewhat

more or less a veteran of the crazy things that happened in the military,

I had my uniform packed on the top of my seabag and within an hour was

out the gate and on the bus and in the town, calling your mother to tell

her what had happened. She started making plans immediately to come

down to Texas and live. We were eventually to get a place on the

base and lived in military housing right at the very end of the base along

with all the rattlesnakes, tarantulas, leaches, and all the other amenities

of Texas country life. But this was a reprieve.

-

We were to change from a dive-bombing group to

mostly fighter planes, and this was the reason for the stopover.

Just the headquarters and service squadrons were kept, and really all new

people came in as far as the pilots were concerned, because these were

all fighter pilots, rather than dive-bomber pilots. We started a

totally new phase of training at that point.

-

We were to make a number of friends while we were

there at the base, both husbands and wives, and some of those friends were

to join us again in California at a later time, hunting for hotels and

stuff. While we were at Eagle Mountain Lake, we were able to go into

town in a big old open-air rickety bus and it was really a very pleasant

way to live. We were there during the period of time that the first

invasion across the (English) Channel was made, (known as) D-day.

We ended up getting a little dog called Pug, which eventually your mother

was to take home with her and became kind of a semi-family with our dog.

-

Mom and Pug (Personal Archive)

“We ended up getting a little dog named Pug.”

-

One of the drawbacks was the fact that this was

summertime and the temperature was over 100 degrees pretty much every day

for about 11 days. So living in a barracks with a metal roof and

that hot sun didn’t exactly make for comfortable sleeping at night, so

we don’t look back on that part of it as being all that great.

-

When we finally did get orders to move on, we

had a party to say our good-byes. We partied all night, and the next

day ended up on the same cattle car-type train with the women standing

in this little town of Newark, Texas, saying good-bye again.

-

We went from there to San Diego, with the wives

going home. But when we got to San Diego and found we were going

to be there for a little while, they all came traipsing back with the drawback

being that there were not enough hotel rooms. I believe the limit was three

days that you could stay in any one hotel, then you had to move out.

All the time we were there, we made a circus of running around from hotel

to hotel to keep having a place to live. Eventually the word came

to go back out. This was to be the trip that was to end up at Okinawa.

-

So I was back aboard ship and back out into the

Pacific. We did stop at Pearl Harbor and I took quite a bit of ribbing

when we got there because I had made it a point to tell all the guys about

what Honolulu was like, with row after row of houses of prostitution and

with line after line on the street of guys waiting to make use of the places.

This was one of the things that really stuck in my memory because I had

never seen anything like it before nor since, to the point where actually

you could smell in the streets exactly what kind of a street it was because

of all the intermixed odors coming out of these various rooms, none of

which had air conditioning. But when the Navy ship came into port,

about half of the crew would get in line and they would stay in line all

day long, going up and coming back and getting in line again. When

we pulled into Pearl Harbor this time, there were people on the docks selling

the Honolulu Advertiser, the #1 newspaper there. I bought a paper

and the headline was about 2” high with two words.... “HOUSES CLOSED”.

-

We were to see much of the other side of Oahu

on this trip because we were assigned to the airbases at Ewa and at Barber’s

Point, which is on the opposite side of Oahu from Honolulu and Pearl Harbor.

I don’t remember exactly how many days we stayed there, but that was to

be our initial point in the Pacific and we did very little. (While

there), we were allowed to have two beers a day, and while I didn’t drink

beer, I would give my chips to somebody else. In fact, I have a couple

in my scrapbook. The weather was lovely, the scenery was lovely,

and we were just killing time waiting to see what would happen next.

Incidentally, if you’ve read the story of Pearl Harbor, that’s the first

area that was really bombed because the planes came in that way.

It was a Marine and Naval airbase at the time of the original Pearl Harbor

bombing.

-

When we left Pearl Harbor this time, we were in

for a long, long trip. We were a floating reserve air group for a

backup to the original air group people who were going into Iwo Jima.

We just simply were on the ship, killing time floating around the Pacific

waiting to see where and if we were needed. We eventually ended up

back in New Hebrides at Espiritu Santo. We had a stop en route at

the Palau Islands, first lying in anchor a couple of days off the island

of Babeldaob, which was occupied by the Japanese but never reoccupied by

the Americans. The Japanese people were just allowed to sit there

and more or less vegetate without any supplies while the fighting took

place on Peleliu itself.

-

We moved around, eventually getting ready to move

on and we pulled into the harbor area long enough to drop off 30 some men

as replacements for the people killed or wounded and out of action at the

Peleliu airbase for the Marine group that was there. Capt. Cannon,

my boss and friend, had insisted that he and I go ashore and see if there

was any mail. Actually, he just wanted to go and participate in whatever

was going on there. He was a guy who was always ready to run into

danger, and do whatever was exciting. So we went off the boat with

me carrying a mail sack and a rifle, trying to go down the landing net

because we were quite a way out at sea. It wasn’t a really good harbor

there. We got into a small boat and went ashore. We finally

made our way to the airfield, not without some problems because the Japanese

were pretty well ensconced in

-

what was called “Bloody Ridge”.

-

“So we went… carrying a mail sack and a rifle.”

(Personal Archive)

-

This was a big ridge that dominated the airfield

and the Japs were holed up in caves there and quite often snipers would

knock off people walking around the airfield or to the airfield, as we

were doing, or coming in from the beach to the airfield.

-

There were shots fired, but nowhere near

us, so comparatively that was an uneventful trip too. We didn’t get

any mail there because nobody knew we were going to stop there in the first

place. In the second place, the only mail that they would normally

bring to an island like that, that was in a combat situation, was the bare

minimum of mail for the actual guys doing the fighting. But we got

to see a little bit of what was going on still. The island still

was not secured, but we were able to get back on our little boat and leave

the place, thank goodness, and get back on the ship to take off again on

our nomad journey.

-

My scrapbook tells how many days we were on the

ship, but I believe it was 96, and as happened to us at Guadalcanal, we

had nowhere near enough food. (See Appendix 3) We had gone with about

three weeks worth of supplies, but with 90 some days wandering around,

of course the food ran out. We broke into the storage that we were

to use if and when we were in combat, the C-rations, the K-rations, and

the other emergency supplies. We did stop several times on our roundabout

way, once at Ulithi, and there we went ashore for what was called a beach

party, with a chance for those who wanted to swim do so, and each man was

allowed two bottles of beer which they had obtained somewhere. We

did the same thing when we had stopped at Eniwetok. There was certainly

some food brought aboard at each of those stops, however, very little of

it filtered down to the enlisted men. The civilian crew on the ship

and the officers used up pretty much everything in the officers’ mess.

-

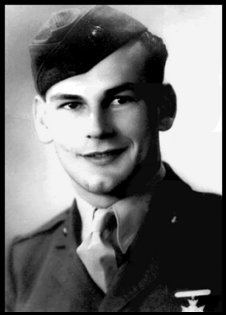

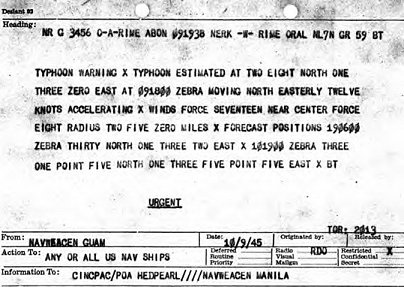

We also had quite an experience on this trip,

in that we were caught in a typhoon where the winds were so great that

the waves often were above the top of the mast on the ship. In fact,

we did lose two ships out of the convoy that we were in at the stage that

we went through the typhoon. They just disappeared. The winds

of the typhoon were over 100 miles per hour and none of the Marines were

supposed to be allowed up on deck, although we all snuck up to take a look

at one stage or another. You had to have a rope tied to you so you

wouldn’t get blown or washed away when you stuck your head out of the hatch.

-

Radiogram Warning of Typhoon 1945

“You had to have a rope tied to you so you

wouldn’t get blown or washed away.”

-

Eventually, we arrived at Espiritu Santo in the

New Hebrides Islands, I believe the islands are now called “Vanuatu.”

We had pretty decent living quarters there, in fact, the mail crew were

assigned to a Quonset hut type building, a metal building where we had

room for the post office at one end, and our bunks at the other end.

While we were still on the ship, we knew that when we finally got to a

resting place, we would have some mail, so that we had the parachute riggers

on the boat make up a big cubbyhole-type thing where we could sort mail.

The idea was that we would eventually tie it between trees or whatever,

so that we would have this semi-permanent place to work.

-

When we finally arrived at Espiritu, there was

a big stack of mail, and we were told to get cracking as soon as we got

on shore to get the mail out and worked all night, and in fact had a mail

call at 3:30 a.m. or so and didn’t find anybody asleep. Everybody

came out for their mail. As I said, we had pretty decent quarters.

This was a more established base than we had been used to. We were

to be there eventually over Christmas and New Years. They had movies

every night, sometimes the same ones two or three nights in a row, but

at least some movie every night.

-

During the Christmas/New Years holiday, Bob Crosby

(Bing Crosby’s brother) was there with his band and with some other acts.

They put on a show several nights, and of course the place was absolutely

packed all the time. (See Appendix 4) We also ate much better here

then before because I’d made friends of the cooks. And so we were

to have for the very first time in my life, and for most of the men out

there, pizza. Surprisingly you might not realize that before WWII,

there was no such thing as pizza. With all the places there are now,

it was introduced during the war in New York where these two cooks were

from. They would make great big commercial pans of it, enough to

feed maybe 20 people, and bring us over a pan on which we’d feed for a

week. They’d also sneak us steaks once in a while. In fact,

on New Year’s Eve, that’s what we did... sit and cook the steaks in the

barracks. We had gotten some stove materials some place and were

able to make a wood fire in this stove and cook the steaks in the middle

of the living quarters. Capt. Cannon, who was our intelligence officer

and my boss in the mail department, brought us over a bottle of booze and

while none of us at that point in life were much of a drinking crew, we

sure appreciated that. It made our New Year’s even more special.

However, he brought over something besides booze... the news that, as intelligence

officer, he was aware of... that we were being assigned to go ashore at

a place called Okinawa.

-

Like Guadalcanal in the early days of the war,

we didn’t know really where Okinawa was. However, when we looked

at a map we were ready to fall through the floor because it looked like

it was part of Japan and of course, it practically was. We had to

keep this news quiet from anybody else, but it didn’t make the nights any

easier knowing that we were going to have to go into the Japanese’ back

yard on this landing sometime later. It was, of course, eventually

to be on April 1st.

-

We finally moved to an airfield in New Hebrides

called Luganville, and close to it there were some commercial huts, in

fact there was a Post Exchange setup in one where we could buy things.

(See Appendix 5) By this time I had a car to use to haul the mail

around and we found that there was a little restaurant back up in the hills

where, I think it was around $3.00, maybe less, we could get a steak and

a bottle of wine. So we would scoot up there every so often and have

ourselves a dinner out. That was a little bit of semi-civilized living.

-

It was also at this time that I became a Catholic,

had first communion and a baptism at a little mission in the hills overlooking

the bay. The priest that was there was actually the archbishop of

the whole Pacific-island area. There was no separate Catholic Church,

as such.

-

St. Michael Mission at Luganville 1945 (Personal

Archive)

-

So, while we had a high echelon priest,

the mission only seated twenty-two people so it wasn’t exactly a big church.

-

After the more-or-less uneventful life at Espiritu,

we boarded ship again to go to some strange place, and unfortunately, I

knew it was Okinawa. Our first stop was in the bay, just outside

Guadalcanal, where we stayed for a couple of days aboard ship and weren’t

allowed to go ashore or anything, but evidently were waiting for a convoy

to form. We left the Guadalcanal area with a number of ships and

went to a place called Manus in the Admiralty Islands where again, we stayed

for days, but did not go ashore. Here again there was a group of

ships joining us to make for an even larger convoy. Then we went

to Ulithi again, and were there when a sub managed to sneak under the protective

net at the harbor and sank a tanker a couple of ships away from us.

It really scared the daylights out of all of us. We also were there

when the U.S.S. Franklin, one our bigger, newer carriers came in with a

hole completely through the whole side of the ship, and a great big area

missing out of the landing deck.

-

-

-

USS Franklin Afire

“It had killed very, very many men and had

seriously damaged the carrier.”

-

As we were to find out later, it had been

hit by bombers while the planes on the deck were armed. The planes

had blown up and the bombs had blown up and so it had killed very, very

many men and had very seriously damaged the carrier. (See Appendix

6)

-

So, from there on to Okinawa. Easter Sunday,

April 1st we went ashore, and while we were not assault troops, we did

go in immediately on that day. Part of us aboard the ship, and part

of us on a landing craft. I was on the ship. The landing craft,

a LCT I think they were called at that time, was hit off the island and

some of the men were killed, but the rest got ashore safety. We had

no problems. The first night staying on the beach again, wondering

what was going to happen next with no Japanese opposition. Just that

incredible fear of the unknown.

Invasion Beach Still Under Fire at Okinawa

– April 1945 (Personal Archive)

“That incredible fear of the unknown.”

-

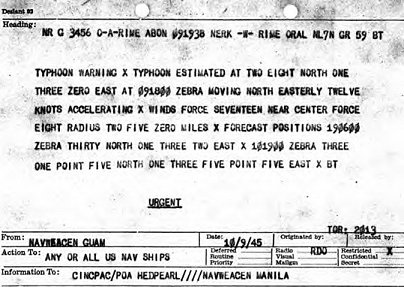

The next day without incident, we were to go on

to a little town called “Kadena” where there was a small airfield and this

was to be our new home for our planes. They followed us in very shortly,

and while the airfield was gradually extended, the eventual Kadena airfield

which is in existence today, was to be made into a major one and we were

later in the war to see B-29 planes take off of the new extended runways.

-

Shoulder Flash for the Second Marine Air Wing

Note: The Third Marine Air Wing Became

MAW II when transferring overseas.

-

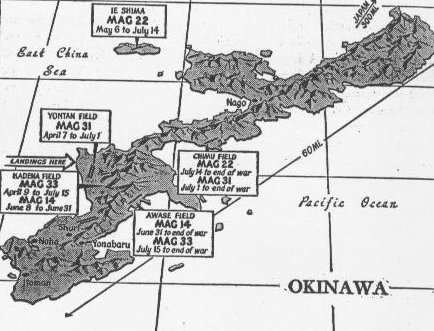

The main airfield at that time, though, was in

a place called Yontan, and this is where the major planes came in with

mail. We had to drive every day from our airfield to Yontan to pick

up mail and I had made a special point of having a mail call every day

at the same time, whether or not we got mail.

-

Okinawan Air Fields – April 1945

“We had to drive every day from our airfield

to Yontan.”

-

We would go up every morning and sometimes

the road was hard to get through because the Japanese were still shelling.

But we did maintain an everyday mail call; sometimes it was only one or

two letters... sometimes with bags of mail. We had our tent built

in what had been a revetment, or sheltered area, for the Japanese planes.

This wasn’t too bad, except that we had another so-called Pistol Pete,

an artillery piece that fired sporadically at the airfield area, including

the revetments, which they of course knew the location of since they had

used them. It wasn’t at all unusual to have to get out of there in

a heck of a big hurry.

-

We also had some air raids. I can remember

one night when we were in there and the alarm went off and the rest of

us got out and went into the trenches that we used for foxholes.

John Condon, who was a friend of mine and an ex-boxer and an ex-boxing

manager from Boston, was one of the souls who said he was not going to

be inconvenienced by running out and jumping into a ditch all the time.

He got quite a little surprise when one of the planes came in strafing

and shooting holes through the tent. Suddenly, Condon was sitting

on my back! He came tearing out of the tent as soon as the bullets

started to hit around him.

Night Raid on Yontan Airfield

“The planes came in strafing, shooting holes

through the tent.”

-

We were also under one of those attacks, listening

to the radio one night, and had to roll down the hill into the ditch with

that portable radio when we heard the news that President Roosevelt had

died. That really shook us up. We had a very large tent that

we used as a mail tent and with all the shelling going on, I finally had

found a cave in a ravine that was dug into a hillside on the side from

which they were shooting, which would protect us from the shells because

they would go over our heads. So I went over there to live rather

than living in the tent. I was somewhat demoralized one night to

go over there and find everything gone, particularly since the next night

they found one of the Japanese that had infiltrated our camp and was captured.

So I didn’t go back to the cave anymore. I figured if it was a question

of shooting at me or somebody finding me dug into a cave where they could

trap me, I would take my chances on the tent and on the shelling.

-

I had one experience, which was different than

others there, because in sorting and operating the mail operation, I had

access to a censor stamp. One of the officers would send us the mail

uncensored and asked me to stamp them for him, and I did this once in a

while as I did for Capt. Cannon. But when we got the V- mail, the

censor stamp had to go on the letter before the flap could be sealed, and

this Capt. Corlette, who was our law officer finally sent me a nasty note,

called me all sorts of names, because I would no longer do his censoring

for him and asked him to be the one to seal the letters so that if he wanted

to check them, he could check them. I finally went storming out one

day (and met) Colonel Dickey, our commanding officer, coming from the mess

hall. I told him about my problem, showed him the note which called

me a son-of-a-bitch and told him that this Capt. Corlette was not an officer,

nor a gentleman, and Colonel Dickey said he would take care of it.

I never heard another word from him, however, Capt. Cannon told me the

next day that Capt. Corlette was now the mess officer. He had been

demoted from law officer.

-

We didn’t have too many men killed or hurt by

all the shelling and the bombing, but we had a friend of mine named Ronald

Stern killed in his foxhole one day by coral from the airfield which, when

they were blasting, a big chunk came and hit him on the top of the head.

-

All these things were coming second-hand to me

from people who were getting their mail while I was still working sorting

mail and didn’t have a chance to read my own. So I found out second-hand

both about the fact that we were going to have a child and also that Tom

was born. We moved from Kadena shortly after that to another part

on the other side of the island to a place called Yonabaru, which is on

the China Sea. I hadn’t mentioned it, but all the time we were on

Okinawa, we had a great deal of rain and we had to struggle through the

mud day after day after day, and it seemed to go on forever, particularly

with driving the mail truck on these muddy roads and on the side of cliffs.

It wasn’t at all unusual to find the truck ahead of had simply just slid

right off the edge of the road. But the weather got even worse because

we had a typhoon and winds in this were pretty close to 200 miles per hour;

the worst up to that date that they had ever had in the Pacific. It blew

ships up on shore as much as a mile inland. It took our Quonset hut

that we were in and bent it up in the middle so that half of it was still

sitting on the ground and half of it was at right angles sticking up in

the air. (See Appendix 7)

-

-

MAG33Headquarters Quonset Huts on Okinawa

1945 (Personal Archive)

“Half of it was still on the ground and half

was sticking at right angles up in the air.”

-

We went out of the mail hut in order to find a

safer place and climbed into a deep ditch, but we weren’t in that for more

than 20 minutes to 1/2 hour when the ditch filled up with water and it

became a question of either drowning or getting back out. So that

was a terrible, terrible day because there were pieces of steel flying

through the air, there were people killed - I saw one guy who had been

hit in the chest with a steel beam from one of the Quonset huts and it

had simply gone right through him. But like all things, it finally

ended.

-

While we were on Kadena we did have a kamikaze

attack one night, which had our airfield bombed by a few planes, but with

some 14 or so planes going directly over to the Yontan airfield, landing

on the field, (and) all the Japanese getting out and running around blowing

up planes and starting fires. It was a real hellish night because

nobody knew where they were or whether they were on our field too, or just

what to think about the whole thing. Eventually, all of them were

killed or captured, but they created a great deal of damage and destroyed

dozens of our planes.

-

While Kadena was to become a big enough airbase

to house even the B-29’s, they really weren’t stationed there. The

airfield was used as a stopover place for those planes that flew from Saipan,

or Tinian, and bombed Japan and then didn’t have enough fuel or had damage,

or whatever. They landed in Kadena rather than trying to make the

much longer trip back to their base. Included in those B-29’s that

did that was the one that dropped the second atomic bomb on Japan.

-

Bockscar-Plane flown by Major Sweeney on Second

A-bomb Drop

(Nose Art Added After Atom Bomb Mission)

-

I was there when they came back and the

Major who was the pilot was an absolute shaking mess. He just couldn’t

believe the damage that the bomb had done (that) they were able to see

as they turned away from Nagasaki. (See Appendix 8)

-

The Crew of the Second A-Bomb Drop in

Front of Bockscar

“He couldn’t believe the damage the bomb had

done.”

-

Later in the war we were still going up to Yontan

to get the mail, and I was there the day that McArthur came in after the

war had ended on his way up to the surrender ceremonies. We were

happy to still be alive at that point, because that day when the war did

end, all the Navy ships out in Buckner Bay (which was the main Navy anchorage

just outside Yonabaru airfield) started shooting off their guns when they

heard the war was over. We, unfortunately, were on top of a

hill maybe 200 feet up from the beach and many of the shells were going

over at about 205 feet. So we spent the whole night cowering in a

hole so that our own guys wouldn’t kill us. That was another experience

that I don’t want to go through again.

-

As the war ended, they started to bring troops

back home very rapidly. They set up a system where if you had a certain

number of points that you gained by being in the service for a particular

length of time (with) overseas points counted more (towards going home).

I believe you needed 85 points to go home in the first group and I had

145. But (I) forgot about the fact that I had signed up as a regular

when I joined the Marine Corps. So I was told that I had to stay, which

I did, and watched a lot of the other guys go home ahead of me. But

life wasn’t too bad at that point. We were getting pretty decent

food and everybody was in a relaxed sort of mood.

-

The biggest question was what to do with the supplies

and everything that were going to be left over... whether they were to

be packed up and shipped back to the States, or left, or dumped, or whatever.

There also was the matter of the basic office work and the medal routine

that went on during each of the major battles. Most of the officers

wrote commendatory notes for the others, and got their medals for meritorious

service and stuff. So one day, Condon, who was the non-commissioned

officer made assistant to our colonel, Colonel Sam Jack, came to me one

day and asked me if I wanted the silver star or bronze star -- that he

could simply write up the ticket for it. I laughed at him, but he

said he was serious, that it was up to me if I wanted it. He was

going to have one written for himself. I said no, I didn’t believe

that was the way to go about it. I did eventually end up with a commendation,

even without asking for it. I got the commendation from the commanding

general of the Pacific for my various runs to the other airport for mail

when they were shooting at us occasionally and for conducting the regular

mail call every day which supposedly contributed greatly to the morale

of the troops. (See Appendix 10)

-

I keep a picture of me, Condon, a warrant officer

named Davern and another friend of ours in my scrapbook. We are sitting

outside of our command car on a section of Okinawa where we had gone to

look for my friend, Bernard Young, who was the commanding officer of a

tank corp. This was earlier in the war. While we were

hunting for Young, we didn’t realize that we had gone beyond the end of

the American lines and had passed Young and the others who were in the

forward lines. So we were sitting out there, talking about the fact

that we were so dumb that we would go barging off into enemy territory

and not know about it, and particularly have nerve enough to sit down and

take each other’s pictures and have lunch.

-

-

Clevinger, Dunis, Baird, Davern & Condon

Resting Beyond the Lines (Personal Archive)

“We didn’t realize that we had gone beyond

the end of the American Lines.”

-

Young eventually came down to visit us too, because

being in a forward echelon he was short of supplies, particularly communication

supplies, and he knew that I had been in this radio and telephone group

in my first trip out. So my two friends who were the communication

radio non-commissioned officers helped me get together a batch of wire

and phones and other equipment that Young needed for his tank corps camp.

He and I had now bumped into each other several times during the way.

-

The communication men had made life a lot more

interesting there too, because they had a radio with direct communication

with all of the air-to-ground operators and so we were able to listen to

our fighters, particularly the night fighters, as they were up in the air

and in combat, and to some extent we could pick up communications from

ships off shore. As a result, we were better informed about what

was going on around us than anybody who didn’t have access to the radios.

-

There are also pictures in the scrapbook of the

surrender of the Ryukyu Islands, Okinawa and the rest of them, with a general

who had been one of the best known generals in the war, operating in the

China/Burma/India part of the war, General Vinegar Joe Stillwell.

He was there to accept the surrender of the Japanese general, whose name

I don’t remember anymore. But we do have those pictures of the whole

surrender ceremony.

-

Surrender Ceremony of Ryuku Islands

“Vinegar” Joe Stillwell and (Japanese) General

Nomi

-

Since I had enlisted on January 19, 1942, this

meant that I wasn’t going to get out until January of 1946, but finally

there were enough ships available that I was able to leave for home toward

the end of November and had a very pleasant trip back because when the

ship came into Okinawa, it was about 2/3 loaded with people from China,

mostly missionaries, but also a couple of hundred other people who had

been in Japanese prison camps as well as most of the missionaries who had

also been prisoners. Talking to them about China on the way home,

we used to stand at the rail and gab almost every evening and sometimes

all day, about their life and the differences in what they were expecting

to find when they got back to the United States. Most of them had

not been back for 8, 9, 10 years. (See Appendix 9)

-

So we came back to San Francisco through the Golden

Gate Bridge.

The Golden Gate Bridge

“It is quite an experience.”

-

Of course the experience that that is, I suppose

like people approaching the Statue of Liberty in the Atlantic coming to

America for the first time, or coming back after a long absence.

(It is) quite an experience, even though it’s just an old bridge.

We went through the usual medical exams, etc. there before being sent home,

and as with the first time coming back from overseas, we were entitled

to a 30-day furlough. So I came home, and it was quite an experience

seeing Tom for the first time, and looking forward to starting a life really

for the first time as a civilian married man. I found that I didn’t

want to go back to camp, although I knew I had to, to be discharged.

I sent a telegram telling them that I would be of more good at home to

my family then I was to the Marine Corps, and starting packing and getting

ready to go back, knowing full well that they would never OK such a telegram.

So I was immensely surprised when we did get the answer, telling me to

stay home until it was time to be discharged. Eventually I was to

end up in the Marine Corps until January 22nd because of not going back

earlier. I would’ve signed up in the Reserves, because it sounded

like a very good idea at the time, but the Lady Marines were too busy.

I finally decided I wouldn’t wait any longer and started for home. Almost

everybody who signed up in the Reserves in those days, ended up in Korea

and most of them, of course, ended up wounded or killed in the disaster

that Korea was. So, by the sake of some gal being too slow, I ended

up not having to go to Korea also.

-

When I got home we moved in with Grandma and Grandpa

Mack in a house that they rented in Lakewood, and thanks to their good

heartedness, we were able to stay there until finally they moved a group

of barracks to a housing area that they created for veterans in Lakewood

where the present Lakewood City Hall is located. We got an apartment

there which was half of one of the same old metal barracks buildings that

we had lived in Texas and were common on military bases, but updated a

little bit, but still just metal shacks. But (it was) a great place

to live when you couldn’t get a house to rent or had no money to buy a

house. So that was where we lived until we finally came to Parma

Heights.

-

Lakewood Veterans Housing

“Where we lived until we came to Parma Hts.”

-

It’s impossible, of course, to explain to anybody

who was not alive at the time just what

-

those war years were like, for anybody at home

or anybody in the service, but particularly (for those) in the service

and in the combat areas. In many ways, I was able to see pretty much

the beginning of the Pacific war and the end by going to Pearl Harbor as

early as I did and seeing the ships that were still being hauled out of

the water, and even men still being hauled out of the water, and the terrific

damage that had been done and the fact that there were so few men at Pearl

Harbor or on Oahu to defend the island. If the Japs had sent in landing

troops, they would’ve had almost no opposition. On the other islands

of the Hawaiian Islands, no opposition. There just were no troops.

We had nothing in our favor much in the Pacific at that time, except for

the fleet, and of course most of that was lost on Pearl Harbor day.

It seemed pretty much luck to stop the Japanese at Midway and then into

that Guadalcanal landing, where we had, I suppose, between 20 and 30 ships

but no more than that, and all the ragtag collection of troops that we

sent in there. And then to go and be part of the Okinawa landing

where there were ships as far as the eye could see on the morning of April

1st. I couldn’t believe it. I don’t know what the count was,

but I believe I’ve read it was over 500, but it seemed like the ocean was

covered with ships. It seemed like everybody in the world was there.

So we had made that come back from what looked like a total losing operation

at the beginning to where, at least in the sense that most people use the

word, we won the war and the war was over. Of course, as I’m dictating

this into the tape recorder now, the Japanese have enjoyed a great deal

of prosperity and maybe we lost a big part of the war after all.

Dictated by George J. Baird

Circa 1993

The End

Please

take the time to share your thoughts

by signing

my Guestbook

E-Mail:

WBaird721@aol.com

Oral

History of Service Volume I

(click

to enter)

(Return

to Main Page)