|

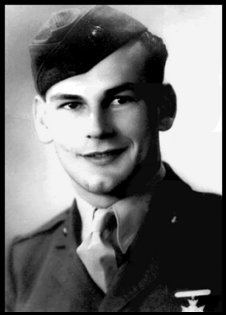

Oral History of Service South Pacific Theater 1942

George J. Baird “Long may the tale be told in the Great Republic” Winston

Churchill speaking of

|

|

- I suppose

you really need to have a general picture of the times before the war in

order to get an idea for a starting point. As you know, we had just

come out of the depression and I had graduated from high school in 1938,

had not been able to go to college, and groped around for jobs. At

the time when the war had finally started, I had been working for Fanner’s

Manufacturing Company down near the zoo off of Pearl Road, and had what,

at that time, was a very high paying although a very menial job working

in the shipping room at a plant making parts that were used in the production

of various kinds of steel equipment which of course included, at that point

with the military buildup going on, things for the government. Because

things were busy, the reason it was a fairly high paying job was because

there was so much overtime and rather than working the normal 40 hour week,

we were working upwards of 56 or 57 hours a week and getting time and a

half or double for the extra hours and bringing home some pretty good paychecks.

Fanner’s Manufacturing (1952 picture)

“At the

time the war had finally started,

I was working

for Fanner’s Manufacturing.”

At the time

of the attack on Pearl Harbor, I had been given a number in the draft arrangement

for the Army, which at that time was in effect as the Army military was

building up. You were assigned a number and then called in relationship

to where your number was in the list of the lottery, and I had a number

that was called fairly early so that I was due in December 1941 to report

for an Army physical and eventual enlistment in the Army. I did go

for the physical, and had some minor problems, but generally as far as

I knew I’d been accepted. But I wasn’t all that happy and was just

biding my time when of course, on December 7th the attack (was made) on

Pearl Harbor.

At that

time, I was dating your mother and had a date that Sunday on which we were

to drive Russ and Tate to Kent (State University) where Russ was going

to school. He and Tate had been dating for a long time so it was

common for the four of us to make the trip to Kent since Russ didn’t have

a car and I did. We, of course, all were very upset about our futures

and/or lack of futures because of Pearl Harbor when we heard about the

attack. None of us really knew where Pearl Harbor or Honolulu was.

We knew generally where the Hawaiian Islands were, but that was about it.

We had known that there was the danger of war all the time, and this was

the reason the military had been building up gradually and calling people

into the service under the draft laws. So that Sunday afternoon,

we went down to Kent and sat in the Robin Hood Restaurant, which was the

local gathering place for the students, and talked about what we could

do or shouldn’t do and should we go in the service.

The Robin

Hood Inn, Kent Ohio

“We talked

about what we should do.”

Russ

questioned whether he should quit college and all of us wondered what the

future was going to hold for us. The next day, I took off from my

job to go sit in the car and listen to the radio when President Roosevelt

made his declaration of war at 1:00. (See Appendix 1)

One thing

led to another, and finally I decided to try and enlist in the Marine Corps

because I thought the Marine Corps would have much better training than

the Army, and theoretically, I would be better off. Some of my friends,

Frank Glover for instance, my closest friend, and Meryl Young, a friend

of his who had become a friend of mine, sat and talked about it and they

both thought I was crazy to consider going into the Marine Corps.

I was just going to end up getting killed right off the bat. They

were opting for waiting and delaying as long as possible and going into

the Air Corps and getting the long training that entailed and the professional

training in becoming an officer at the end of it, where I would be going

into the private (enlisted) sector. To make a long story a short

one, Glover was killed in Europe. He had been shot down once over

France and brought back by the French Resistance only to be sent up again

on the premise that he shouldn’t be allowed to sit and brood over his problems.

Then the very first flight back out again he was shot down and killed somewhere

over Germany. Meryl Young walked into the propeller of an airplane

and was all chewed up and never able to go into any kind of real work after

that at all. He was sent out of the military, pretty much a cripple.

So, while I ended up with some problems later on, at least I came back

and was able to have a normal life after the war.

When I

enlisted in the Marine Corps in January, or attempted to enlist, they told

me I couldn’t see well enough and would have to get glasses. So I

marched across the street and found an optician in downtown Cleveland off

Public Square and had my eyes tested and ordered glasses which they made

up for me in a couple of days. I went back and took the Marine Corps

test again. As an oddity, I never did put the glasses on and didn’t

in fact put them on after that, although I carried them with me and eventually

they were broken by a bomb explosion on Guadalcanal. That was my

first brush with eye problems.

The 19th

of January (1942), when I went into the Marine Corps, we were to leave

that evening for Paris Island, South Carolina. So I was signed

in and was told to report to the Terminal Tower, (Train terminal in downtown

Cleveland) to be taken on to boot camp at Paris Island. Somewhere

between the time that we were given these instructions and we showed up

there, there had been a change. After we got on the train, we found

that we were heading for the West Coast to San Diego. While my mother

and dad had been down at the terminal to see me off, the first inclination

that they had that I was heading other than to South Carolina was when

I sent them a postcard from somewhere in Arizona (and said) that I would

write to them again. I couldn’t tell them any more than that because

of the fact that we were only allowed to give basic information at that

stage and couldn’t divulge what bases we were going to.

When we

got to San Diego, we met our first DI (drill instructor) when we got off

the train and were marched down the street to a bus, which took us to the

camp. The recruit depot in San Diego was a big sprawling affair near

the Consolidated Aircraft Manufacturing Plant, where a lot of planes were

built in that stage of the war. The camp had views which were absolutely

terrific in the morning looking up into the mountains when you had to get

out for morning colors. But other than that, it was a really rough

sort of typical bootcamp like you read in stories. Nothing was easy,

and they bullied you and screamed at you until you felt that you were ready

to go jump off a cliff if need be. However, the bootcamp was reduced

from the supposed 13 weeks, which was the minimum, to six weeks.

Then I was assigned to the radio and telephone school for, again theoretically,

another 6-13 weeks training period, only to find out after 3 or 4 weeks

that there was an opening for a couple of the men in the class to go overseas.

While we had no real notion of where it was, we all assumed it was Pearl

Harbor. After everybody in the class except two or three of us volunteered

to fill those two slots, they decided that they couldn’t make a choice

any fairer than simply pick the first two guys in the alphabet. I

forget the first guy’s name, but the second name was Baird. So my

trip was started.

Out to

Pearl Harbor and the Third Marine Defense Battalion, which I joined there.

The Third Defense had quite a peacetime history. From training on

the beaches in South Carolina to China, and back to Pearl Harbor.

It had been overseas quite a while when the war started. Most of

these guys were at that time, I presume, fairly typical Marines.

They were guys who had come into the service because they had been in trouble

with the law, or because they were poor and out of work and couldn’t find

any other job, or they enlisted in the Marine Corps to have something to

do or whatever. But essentially a bunch of, well, not exactly prime

time first class college graduate-type people. As we were to find

out later on in combat, the best kind of guys to be with. Maybe because

they weren’t taught to think and read, and didn’t worry about all that-

just to do what they were told to do and do it well. (See Appendix

2)

My best

friend in bootcamp was a guy named Bernard Young, who later on in the war

was to come back into my life but at that point had applied for Officers

Candidates School when I went to the telephone and radio school.

He finally had gotten into OCS and so was staying behind. I wouldn’t

see him again until later in the war.

We finally

left from San Francisco on our trip as replacements to the Third Defense

(Battalion) at Pearl (Harbor) and were basically assigned to a camp in

the hills overlooking Pearl Harbor called Camp Catlin. It was a camp,

which was in a sugar cane field at the edge of a little salt lake. The

main feature of the camp at that point was a prison camp for Japanese prisoners

of the Pearl Harbor attack and civilian prisoners who had been put into

the camp based on the fact that they were considered enemy aliens.

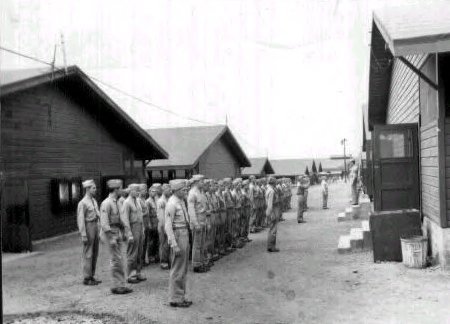

Marines

at Camp Catlin

Camp Catlin

was in the canefields east of Honolulu along the island’s main highway.

Its site selected by a board of Marine colonels, Catlin eventually would

see tens of thousands of Marines pass through its gates into the farthest

reaches of the Pacific as it became the principal replacement and redistribution

center for the Fleet Marine Force.

(See Appendix

Notes on Camp Catlin)

Part of

the job of our outfit was to guard them, but my particular job assignment

was as a telephone man, of course, but directly in Pearl Harbor.

We had to string wire from telephone pole to telephone pole through Pearl

Harbor, and we had gun positions on tops of buildings. We had a machine

gun position, for instance, in our headquarters on what was called the

Aviation Materials Building overlooking battleship row across the channel.

“We expected the Japanese to come back at any time.”

I finally

moved into a little tent that I put up on top of the building. I

stayed there around the clock rather than going back up to the camp all

the time. We ran shifts around the clock on these machine gun positions

which were deemed to be a very necessary part of our defenses because we

expected the Japanese to come back any time because of the damage they

had done at Pearl Harbor and the lack of men. For instance, just

that one Marine Defense Battalion there – roughly 700 men- and some small

Army detachments and Air Corps and Navy air detachments. There really

wasn’t any great amount of defense.

All of

us who were there felt that the Japanese could take over the island any

time they really wanted to. Of course, they never tried. So

life there was fairly uneventful. We were allowed to visit Honolulu

on our off-duty hours and it was a much more attractive town then than

it is now-without all the high rise buildings, just the two main hotels,

the Moana and the Royal Hawaiian. But we also had a 6:00 p.m. curfew

so we weren’t allowed into town in the evenings at all. We were able

to go to the USO where Ray Anthony had a dance band that played.

|

|

They had

a variety of activities. The Royal Hawaiian and Moana were already

set aside for what was later to become called R & R (rest and relaxation)

for people who were on ships that were sunk, or damaged and were sent there

for a break from the war.

Defense

Battalion was a real odd sort of thing in the Marine Corps. It was

meant as it later was to become, a unit for islands like Wake Island, Christmas

Island, and other small islands as kind of a total all-around defense force.

It included a few riflemen, a few machine gunners and artillerymen, and

a few of this and a few of that and not a heck of a lot of any one thing.

It was strictly meant for small outposts. The outfit was also kind

of out of place at Pearl Harbor because the whole island of Oahu was much

bigger than anything that a defense battalion was meant to be part of.

The original First, Third, and Sixth Defense Battalion(s) all started out

as the First Defense and went to Wake Island. The Third Defense stayed

at Pearl Harbor and the Sixth Defense went to Midway. But that was

all formed out of one group, and then with the new people added, was considerably

less when the war started than normal strength so they were comparatively

small groups. So we were out of our real element also at Guadalcanal,

though it was to become a fairly natural arrangement when we were assigned

to basically the airfield defense. Of course, at Guadalcanal the

airfield was the end all and be all of the whole thing. Taking away

the airfield (from the Japanese) and then protecting it and making that

our own base to keep the Japanese off guard was the first really major

step back from Pearl Harbor. It was to become a definite fact in

the Pacific that Midway had been the turning point in stopping them and

Guadalcanal was the start-back and was later to lead to all of the other

things that were to happen in the war.

The next

thing that popped up as far as the military part of the war for us happened

suddenly in the late days of May. We were put on around-the-clock

assignments loading ships. We would work eight hours and be allowed

to rest for four hours, then work for eight more hours, etc. As it

turned out, they had intercepted the Japanese messages about an attack

and we were to end up going to Midway and were loading the ships with ammunition

and stuff to take to Midway. (See Appendix 3)

The Midway

battle, of course, became primarily a naval battle, but like anything else,

when you’re involved it seems like everything is happening to you.

We had some fairly heavy bombing on these little sand strips where there

is almost no place to hide.

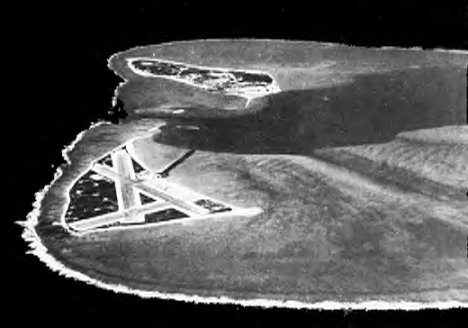

Midway

Atoll

“Almost

no place to hide”

We lost

most of our planes right away. We had a lot of old Brewster Buffalo

planes which were very similar to planes I had seen Jimmy Dolittle and

others fly at the Cleveland National Air Races. They were offshoots

of that plane and with 200 miles an hour slower speed than the Japanese

zero; it led to absolute disaster.

The Brewster

Buffalo

“It led

to absolute disaster.”

The

Midway thing was a revelation because of being the first under-fire experience,

but we went back to Pearl Harbor fairly quickly after the Japanese attack,

which was on June 4th. I believe on the 10th we left to go back to

Pearl (Harbor).

The next

month or so we were still involved in a lot of hectic loading of ships

and so forth, and as we were to find, were earmarked for another trip.

This time we went aboard ship for what was eventually the attack of Guadalcanal.

Nobody on the ship knew where Guadalcanal was, or what it was other than

we were told it was a big island. Just what it had to do with the

war, why we were going there, or what we were going to do, none of us knew.

In the later days of the trip, we were told that the Japanese had an airfield

there, or may have an airfield, or maybe had started an airfield.

Nobody really knew, and that was the problem. If there was an airfield,

it was a problem for New Zealand, Australia, New Caledonia and all the

other places around that were either ours or friendly to us. So we

were in a convoy that involved, at the point we left Pearl Harbor, I believe

four ships. We were later to leave Suava Figi, where we were finally

to see what seemed like a mass of ships. There was the total group

of the battle fleet and landing fleet for the attack. So that was

the base point for the troops who had come up from New Zealand. The

First Division had trained in New Zealand and the Third Defense Battalion

and a group of other people had been picked up along different points.

At that point in the war, the lack of available troops was a major part

of our problem because there just were no troops out there to be pushed

into combat quickly except these small insulated groups and then part of

the First Marine Division. So we were all packed together and became

the basic landing force for the Guadalcanal operation.

The Marine

Corps at the time was a very, very small group. My serial number

for instance was 352410, which is not nearly as many numbers as would be

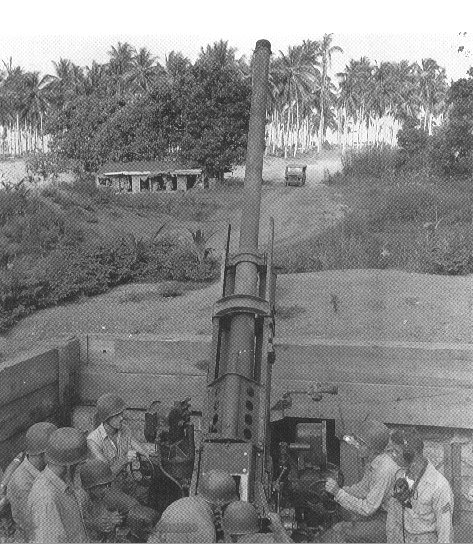

in anybody’s numbering system today. The Marine Corps was very poorly

equipped as compared to the Army. What we had in the way of weapons

were WWI rifles and our 90mm coast artillery guns dated back to WWI.

We had no true anti-aircraft weapon, although we were to use the 90m-coast

artillery as an anti-aircraft gun at Guadalcanal as well as trying to use

our hand-held machine gun. That was almost an impossibility particularly

since the Japanese did not do a great deal of low (altitude) attack sort

of things, and there was no way to reach them at their 23-26 thousand feet

(of altitude). The little bit of so-called field artillery we had

also were WWI, I believe 37mm, and very ineffective sort of weapons.

But at that time, that was the Marine Corps and the reason we were on Guadalcanal

was the same reason that the other troops were there. We were the

only troops available to go.

The United

States was not prepared, so that the landing on Guadalcanal was made theoretically

by the First Marine Division, but actually we were not part of the Division

except as attached for that particular operation. The Second Marine

Regiment was part of the Second Marine Division, not the First. They

just grabbed everybody that was at all possible and this was kind of a

desperation move. I don’t think our military brass knew what the

heck to do and the Japanese were building an airfield there. Once

it was built, they could reach New Zealand and particularly Australia and

islands of theirs. So they decided they had to stop them and they

just reached out and collared everybody that was available. (See

Appendix 4)

Of course,

it’s very hard to describe your feelings when you are young and going off

to war and don’t have the slightest idea of where you’re going, what you

are going to see, what’s going to happen as far as the military part of

it. Whether you are going to end up in a big major landing against

all kinds of ammunition and guns. (You wonder) how you’re going

to be able to get enough nerve to get off the ship, get into that little

landing boat and go ashore, (or) whether you’re going to be too frightened

to do it.

Troops Loading

Landing Craft in the Solomons-August 1942

“Get into

that little landing boat…

or whether

you’re going to be too frightened to do it.”

On

the ship, everyone kids each other and talks and laughs. We had the

crossing of the equator ceremony where essentially any Navy guy would beat

the living daylights out of you as an excuse for introducing you into the

land of Neptune and the fact that you are no longer a “land lubber”- you’ve

crossed the equator.

The only

real work we had to do on the ship was that in order to have some extra

defense on this Liberty Ship transport we were on, we began to rig up our

machine guns around the perimeter and that meant getting up and stringing

up telephone wires from point to point on the ship. That meant climbing

the rigging part way in order to put up the telephone wires. That

wasn’t the most pleasant sort of thing with my problem with heights, particularly

since during part of it I was seasick. Getting up there and rocking

on those became very precarious.

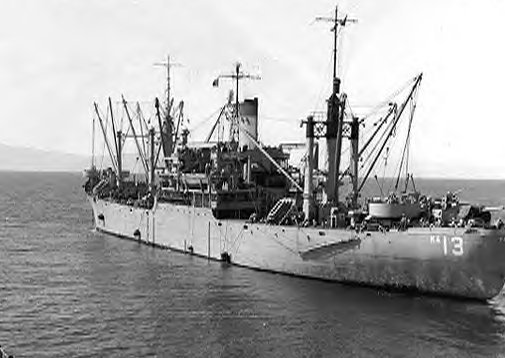

Arcturus

Class Liberty Ship

Like the

USS Betelgeuse, which took the Third Defense Battalion to Guadalcanal

“Getting

up there and rocking on those became very precarious.”

When we

finally got to the area where we were told we were going to be going ashore

the next morning, the doubt, of course, intensified. But the unrealness

of the whole thing was cruising along, and (that) we didn’t see any enemy.

We were in sight of this chain of islands, and we were to move up overnight

so we would be in position. We were trying to sleep and not able to, and

cleaning our guns while trying to calm our nerves enough to stay sane overnight.

When daybreak

came, the cruisers and destroyers starting firing at the shore and carried

on a barrage from just before daybreak. I suppose the first boats

started to shore about 6:00 a.m. We ended up somewhere after 8:00,

climbing down that landing net with our pack and rifle and getting into

that little boat. There was a variety of firing going on and we were

off to shore.

The Japanese

planes by that time had discovered we were there and were coming in and

making their attacks on the boats. I was just generally trying to

figure out how I was ever going to get between that boat and the shore

in one piece. Not being able to swim, I was trying to figure out

what would happen when they sank the boat, which I was sure they were going

to do. But we got ashore and had no real opposition at the beach

at all. This was to be the case on Guadalcanal although half of the

Third Defense had gone to Tulagi across the bay, and had a great deal of

opposition and lost quite a few men. So we were lucky.

Marines

Coming Ashore on Guadalcanal August 7,1942

“We expected

them to bomb us any minute.”

The first

thing we had to do was spread out on the beach and the inevitable- string

the telephone wire and then get the telephones connected so that the various

people of our outfit on the beach could communicate with each other and

also to the beach master, (the controlling officer for the landing), so

we knew what to do from one minute to the next. We got that all set

up and were pretty much in position, looking out at the water and trying

to figure out what was happening next most of the time. We were watching

the Japanese planes as they’d come in. We expected them to bomb us

any minute, but they didn’t. I saw one dead Japanese on one of the

beach areas and one wounded one who was taken prisoner, but no more than

that on the first day.

As I have

told you before, I’m sure, on that first day while we were busy doing that

stringing of wire on the beach, I was to have that experience of climbing

the coconut tree which took all the nerve I had in me. I had to climb

up high enough to get my telephone wire up so nothing would disturb it

and run it from one tree to the next. I got up in the tree, and the

doggoned tree broke off at the base and pitched me out into the ocean with

my climbing spikes on and of course, not being able to swim, scared the

living daylights out of me. But the water was so shallow that I was

able to get myself disentangled from the tree and walk to shore.

The first

night was simply a night when nobody slept. Everybody worried about

what was going to happen to them and we moved just a very short distance

inland; hunkered down in the sand and dug a hole, which we were told to

do and prepared to see what would happen next.

I would

eventually lose track of the days- at that point in time it was all blurred

together and it was not a really major military thing. It was a time

of moving into position for those first few days until we were to become

the defense group on what was later to become Henderson Field. Lever

Brothers, the British company who made all sorts of soaps owned the whole

plantation of palm trees that we were in. I suppose the recap of

the time on Guadalcanal would include telling you what happened from the

first day on and my memory is not that great that I can remember it all.

But I do know that after the first night we lost all of the cruisers and

our transports ran away. That first night, incidentally, I spent

under a Japanese truck without ever thinking about the fact that the gas

tank was filled with gas. They were shooting and I was under the

gas tanks, which was not really the most intelligent thing to do.

The second

night, we had moved up to the fringe of what was to be Henderson Field.

The runway was not complete. The Japanese had started at both ends

and they had a big section in the middle that wasn’t done. We stayed

in a coconut grove right at the very edge of the eastern end of the runway.

Henderson

Field August 1942

“It was

to become the heart and soul and aiming point.”

Somewhere

right after dark, all hell broke loose and everybody was shooting and we

figured they were making a counter attack to drive us to the beaches.

The oddity was that we only had one man wounded. He was shot in the

rear end, right through the buttocks and when the doctors got to him, they

found that the bullet was a 30 caliber American bullet. So he was

the only one wounded and we had to realize the next day that all the shooting

was from one of our groups into one of our other groups. It’s lucky

we didn’t kill each other. There were no Japanese there that night

at all.

When we

finally got our positions on the airfield, there was ridge on the side

closer to the beach from the airfield that had been dug to protect planes

from bombing attacks and stuff. One building which was called the

Pagoda was at one end of this ridge.

The Pagoda

at Henderson Field

“This was

to keep us in hot water pretty much all the time.”

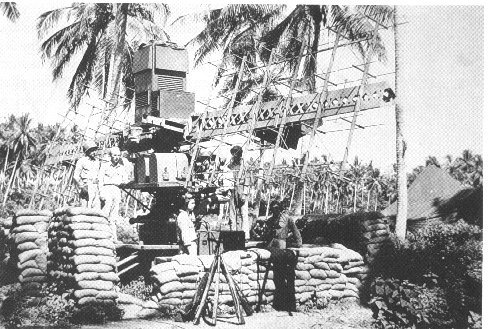

So we dug into the side of the ridge closest to the airfield and built our little lean-to with coconut logs in which we were to put our telephone switchboards. I was to man this part-time along with the other two telephone men. The radar, which we had brought from Pearl Harbor and which was the original radar that had detected the Japanese planes there, we had taken from the Army. There was no other radar available at the time we left, and we set that up and that was at the opposite end of the ridge from the Pagoda.

The SCR268

Search Radar on Guadalcanal

“We set

that up..at the opposite end of the ridge.”

The

communications center was in this little dugout in the hill where I manned

the switchboard for eight hours and then two other men took their turn

so it was manned around the clock. Then when there was an emergency

for some reason, I ended up being the one to be there. The early

days were absolutely terrible because we had no defense against the Japanese

planes coming in because the airfield wasn’t finished. There was a radio

tower in the middle of this little ridge, about 300 feet long. So

it was very concentrated with the radar tower, the radio tower, and the

Pagoda. It was to become the heart and soul of the Japanese aiming

points for their bombing runs and was to keep us in hot water pretty much

all the time.

The routine

at first was work, work, work, and we had no food except for the 3 days

rations that we had started out with. We had to try to figure out

what we were going to do for food, since the Navy ships when they left

had taken most of the food with them. They had thrown some overboard

which floated to shore and some that didn’t. But in any case, we

were left without any supplies. No extra ammunition, no extra food,

no extra medicine, because the Navy lost a group of four cruisers and they

were really battered by the Japanese on the second night and all of our

supply ships had left rather than be sunk. So we were left alone

and lonely.

|

|

The Japanese

planes attacked generally around 1:00 every day and I’ve read that this

was because of the long way they had to fly. They were at the very

limit of their ability too, so they had to leave early in order to get

done there and return to base without any problems before dark. The

general pattern was to come in from the ocean flying pretty high, and then

bomb using our nice little radar and radio towers as aiming points and

target points. So we took quite a beating every day. We had

set up a little tent just below

the dugout

where we slept the night unless there was an alarm. Then we ran up

to the dugout or to foxholes, either one. Shrapnel had come so close

that it had destroyed my glasses and a picture I had of your mother, but

so far hadn’t really done any major damage as far as wounds to manpower

and stuff.

The lack

of modern or up-to-date weapons as I suppose would have made a lot of difference

and yet we didn’t know the difference because we didn’t really know that

the Army had better things than we had. We suspected so, because

most everything in the way of food and stuff we got were the rejects of

what the Army brass didn’t want.

The fact

that we had no airplanes was a devastating sort of thing because the Japanese

planes could just fly in very calmly and drop their bombs and turn around

and go right back. There was no effective anti-aircraft as I’ve mentioned.

The fact that there were no fighter planes to attack the Japanese planes

meant that we were pretty much at their mercy. If they had flown

in a little bit lower, they could’ve been more accurate but they kept beating

up the airfield, which we were trying to complete. The airfield had

not been finished in the center part, but the Seabees were working around

the clock filling in the (center) and making it usable. The constant

air raids and the fact that we had little food and didn’t know what was

going on made it pretty miserable from day to day.

I can still

remember the day when we were told that we were finally getting some fighter

planes and I was standing outside the dugout watching the sky when these

fifteen or so planes came in one after another and we had our first fighter

planes. I was eventually to learn the name of every single one of

those pilots and know which one was in which plane when they took off.

(See Appendix 5)

VMF 223….One

of the first Marine Air Groups

“They were

absolutely terrific”

The dogfights took place a great many times right over the airfield, so that you really had a front row seat to watch and see planes hit and shot down and other planes blow up in the sky. It was quite a big thing and hard to explain really. It is hard to tell you just how much it meant because if you rooted at a football game or a Cleveland Browns game, you are talking about 1% of the feeling and energy that went into rooting for those planes. They did a terrific job. I suppose that while you hear about the British pilots who did so much for Great Britain, I don’t think any group of pilots ever did more for their country than the first Marine pilot group that we had. They were absolutely terrific.

Some of

the few who served so well.

“I don’t

think of any group of pilots ever did more for their country.”

I told you

before about the lack of food and I am sure you have heard me tell the

group before that we were relegated after our week of rations ran out to

what we could pick up from the Japanese stuff that was left behind.

Finally, we ended up with a ration in the morning of a tablespoon full

of rice and a tablespoon of barley. Unfortunately, both of them had

been pretty well sitting in the sun for a long time so sometimes the pieces

of rice were crawling across the plate. They were loaded with maggots,

but that was all we had to eat. I think you probably know that when

I finally got home from Guadalcanal, I weighed something under 120 lbs.

so that obviously it was a diet that helped you lose weight.

One of

the most touching things that happened to me on Guadalcanal was one day

when I was running the switchboard in the morning and everybody else had

gone to the little chow line that was set up to get the rice and barley.

I was watching our SBD’s, our dive-bombers, coming back in from a trip

they had made out to bomb some Japanese shipping that their Navy was sending

down our way. I was watching the planes coming down and one of the

SBD’s came wobbling in about 100 ft. off the ground and right behind it

was a plane that I immediately knew was not ours. I started screaming

into the telephone that this was a Japanese plane. I should have

put the damn telephone down and grabbed my rifle. It was so close

that I could have hit it. But instead of that, they shot the tailgunner,

then just moved right up and shot the pilot and the plane crashed at the

end of the runway. I always thought that if I’d done something different,

grabbed the gun, I might have been able to stop it. That is probably

not the case because by the time I ‘d have got the rifle out, the whole

thing would have been over.

A Dauntless

SBD on Henderson Field 1942

“The plane

crashed at the end of the runway.”

We had some

reasonably good days as I think I have mentioned earlier. When the

weather was bad (which inhibited enemy action) we would go down to the

stream very close to us and that was our only chance to get clean and take

off all our clothes and climb in the water. We would wash our clothes,

take them back and hang them on a tree and let them dry partly before we

put them back on.

As the

days went by, we got more and more the feeling that we would never get

out of there. That we were a sacrifice to try to slow the Japanese

down and that’s all that would happen because they kept getting stronger

and stronger. They kept landing more troops (but) until the 13th

of October; we stayed just the way we were as far as numbers of men.

We couldn’t land anyone else. We didn’t get more equipment.

We didn’t get any more food. We didn’t get anything. Then this

one Army regiment came in on the 13th and, of course, that’s the day I

ended up really out of any part of it. But the Japanese kept getting

stronger and stronger and the only thing that kept us going was the fact

that we kept getting a few more airplanes. They became the major

part of the defense and we also did get more artillery pieces in for our

troops. (See Appendix 6)

Another

Marine regiment came in that was an artillery regiment and they would set

up right in the middle of the airfield shooting the artillery pieces back

into the hills. The Japanese were close enough that this short-range

artillery had to be sitting right smack outside of our little dugout in

order to do their shelling and protect the airfield.

90 mmGun

of the Third Defense Battalion Dug in on Guadalcanal

“We had

no real anti-aircraft weapon.”

But

we kept getting bombed everyday and the bombings got worse after I got

hurt and was in the hospital. As I understand it, so did the shelling

from the guns in the hills and stuff so those things were not all that

well settled when I finally got off the island.

One of

the things that is kind of interesting to know and hard to believe and

hard to realize, I guess, (was that) we had a lot of guys who were shooting

themselves in the foot. We had a corpsman; in fact he was the head

of the corpsman, who was kind of openly homosexual. At that time,

that was a real rarity because they weren’t permitted in the service, but

he didn’t make any bones about it partly to get off Guadalcanal and get

home, but he also broke his arm. Put it across a log or something

and hit it with his rifle butt or whatever and broke his arm in order to

hopefully get sent out with one of us going out on the boats to the outside

hospitals. But that didn’t work because they told him that he wouldn’t

get off the island at any time in the future if the officers could help

it. They would keep him until hell froze over. He was later

on to become a major part of my life. At a later stage, we were in

New Zealand and the battalion got a chance to send home about eight wounded

men, and he was in charge of selecting which guys went home. For

whatever reason, a couple of men who had been overseas in China and for

many months at Pearl Harbor before I joined the outfit, were deemed to

be less hurt and I was selected to come back to the States. So for

whatever reason he picked me and I was glad to be one of them, and eventually

that led to coming back home.

I guess

to summarize the Guadalcanal feeling was that we felt that we were just

a forlorn bunch of people who weren’t going to get any help. We weren’t

going to get out of there and just make the best of a really terrible situation.

I suppose, without those few great pilots and those fighter planes everybody

would have given up completely.

I was in

a better position than most of the guys because in my record book for admittance

to the Marine Corps, the fact that I had worked with the Cleveland Plain

Dealer as a reporter, covering suburban news like Parma and Parma Heights

and so forth, made me kind of a semi-celebrity. Since I also had

the command post telephone and had the one and only radio in the dugout

with me, one of my jobs was to take the radio broadcasts that I got from

the Armed Services Radio and interpret it or read and comment on it.

Every time we got a news broadcast, I would tell the guys at the various

gun positions who had their telephones, and they in turn would tell their

eight or ten buddies who were on that particular position what the news

of the day or the week was. No one else had any way of getting news from

the outside world. So I was the communicator. I was the guy

who passed the word around to the whole battalion.

One other

episode that I might mention about Guadalcanal. It was a strange

thing and something that sure as heck sticks in my mind. I was on

the switchboard one night, and I suppose it was pretty close to midnight.

I was supposed to go off duty at midnight and one of the gun positions

didn’t answer…the one way out on the perimeter. So I finally got

Captain Gill, who was our executive officer and told him about it.

I told him that I didn’t know what the answer was. Whether

we had been attacked by the Japanese or whatever, I just couldn’t raise

them. I kept ringing and ringing. We had a hand-cranked thing

on the phone that caused the other phone to ring pretty loudly. So

naturally, what happened next was that (Captain) Gill said he would take

over the switchboard temporarily and for me to go and find out what happened.

So I had to go across that whole field adjacent to the runway and the airport.

I had to try to remember the password and stay low enough so that nobody

would shoot at me because they saw me. I got all the way across to that

gun position and crawled over the edge and there the guy is; sound asleep.

I got down in the hole and gave him a great big kick in the rear end and

yelled at him to get up! Then I had to crawl all the way back to

headquarters, still hoping that nobody would shoot at me, just because

he fell asleep.

On October

13th, the planes came in from the other way over the mountains. I

wasn’t fortunate enough that day to be working at my regular job manning

the switchboard. I was in a foxhole only to have two bombs straddle

the foxhole and create enough force to drive me underground and to really

bash up the guy who was with me and break most of the bones in his body.

But I was lucky enough to somehow be in that fringe; in-between the two

bombs. The guys had to dig me out because while I had gotten into

this deep foxhole, the force of the bombs had driven all the dirt and stuff

down on top of us from the side of the hill. I don’t think anyone

expected either one of us to be alive. I guess I was an ugly sight

when I got out. When I got up and walked around I guess I was bleeding

from the ears and nose. Most of the pain was in my chest, but the

blood must have made me look pretty bad. I was to go sometime later

that day to the field hospital at the edge of the airfield and was given

a bunk. They offered me some sleeping pills and pain pills.

I just wouldn’t take them. I had a feeling that I didn’t want to

be out of it. I wanted to be able to run or hide or whatever might

be called for and not be peacefully asleep.

Guadalcanal

Field Hospital

“I was

lucky I was not there.”

Sometime

later that evening, I got very uncertain about everything in general and

finally crawled out of the hospital and went into a dugout that they had

for an air raid shelter. Not very long after that the horrendous

shelling started with the Japanese Navy having moved a couple of battleships

and other ships right off the coast. They just pounded the daylights

out of primarily the airfield, but of course all the shorter rounds were

landing all around us. A number of them hit in the hospital area.

We really didn’t think we were going to last through the night. The

coconut logs over the dugout were bouncing up and down and dirt was falling

on us. But eventually it ended and when I did go back to my bunk

area in the hospital, there was a big slab of shrapnel that had gone through

the bunk and down into the dirt below the bunk. I was lucky I was

not there.

The next

several days were almost as bad, although the shelling from the sea didn’t

happen in the daytime, but we were bombed. They also had moved a

couple of artillery pieces, what we called “Pistol Pete”, up close enough

to fire at the airfield. They were going to try to take some of us

out to a rear hospital and tried to take us out on a plane. One of

those artillery pieces blew off part of the tail, so the plane wasn’t able

to fly and we had to go back to the hospital.

Plane Damaged

on Henderson Field in “The Great October Shelling”

“The plane

wasn’t able to fly and we went back to the hospital”

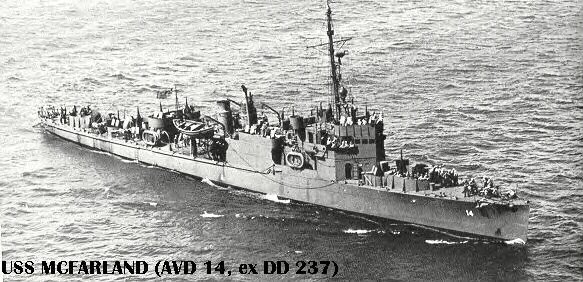

Then on the third or fourth day, they took us out to what was the McFarland. The McFarland was a WWI destroyer that was being used as a combination destroyer, cargo towboat, and all kinds of things to bring in some ammunition and barges of gasoline for the planes. It was the only real supply method we had. There were no tankers or anything. They had these big 50 gallon drums all lashed together on a barge and then they actually had to empty those things pretty much by hand and take them to the airfield where the planes were fueled out of those tanks.

“They dropped a bomb which blew up the back 1/3 of the destroyer.”

We had just

gotten on the McFarland. It had come in the morning and was trying

to unload and then to get out again before the normal 1:00 air raids and

any other air raids later in the day which we had. So we went aboard

ship and they did have food. They were serving ham sandwiches

and I got as far as getting in line and getting a ham sandwich in my hand

when three Japanese divebombers came diving down and they dropped a bomb

which blew up pretty much the back 1/3 of the destroyer. We had had

a submarine alert just before that so that the Navy guys had armed the

depth charges for the sub and unfortunately, those went up with the bomb

and made a really horrendous sight. The gas barge was burning and

flames were as high as two or three houses. It looked like an inferno

that was going to engulf all of us. The ship wasn’t able to move.

Almost all of the steering and propellers were in the back 1/3 (of the

ship), so we were pretty much sitting ducks for anything else that came

along.

The ship

started to sink, so they had given orders to prepare to abandon ship.

They had passed out what few life preservers they had. I guess there

were about 200 Marines who were on there because of wounds or other problems

along with a crew. They had maybe 20 extra life preservers so I ended

up without one. Not being able to swim, I had to just sit there and

wait to see what would happen next. Eventually, a variety of boats

came out primarily from Tulagi and started picking up the men. I

ended up in a PT boat with somebody named Lt. Montgomery and his crew and

was taken to Tulagi. (See Appendix 7) I was helped out

of the boat by, believe it or not, the commander of the troops there.

We were then taken to a kind of a makeshift field hospital to wait and

see what would happen next.

As it happened,

and I think you have probably seen pictures, the McFarland did not sink

and was towed over to Tulagi. In a matter of time, they had built

a rear end for the ship out of coconut logs. They made kind of a raft for

the back end of the ship. It was eventually to go all the way back

to the United States that way and be rebuilt. The crew, particularly

the officers, were given medals for saving the ship. (See Appendix

8)

I keep

harping on the fact that the lack of food was a major part of all that

Guadalcanal experience. I suppose I will mention one other episode.

While I was in the hospital, the day before we were eventually to get on

the McFarland, they announced that they had some food. They were

going to serve it so we all got in a line, waiting for this handout of

food that was coming up. Unfortunately, one of the Japanese cruiser

planes came in and saw this line of men and came down and started to strafe,

and actually shot the guy in front of me. So we got no food.

We were without food until we got on the McFarland, and that ham sandwich

was like gold, which I was going to get there. Then the doggoned

Japanese came back again!

We finally

did get on another destroyer and started (out) for what turned out to be

the hospital at Efate. The trip there was not all that uneventful because

we had several submarine scares. In one case, we actually had a sub

on the surface and to this day I don’t know whether it was theirs or ours.

There wasn’t any shooting between them so I presume it must have been one

of ours. However, we were told to find a barge that was floating

around that had been cut loose from the ship that evidently was under attack.

The barge was let go so the ship could maneuver better. We eventually

found it and they put towlines on it and we towed it, which of course made

the trip slower. While we were supposedly in American held territory,

it wasn’t all that clear in those days. The Japanese Navy had such major

control of the area that they had submarines scattered all through the

area. It wasn’t even impossible that we might not have had a destroyer

there at that end of the island at that time.

The hospital

stay was to be for quite a while. The major injuries and treatment

for me involved my ears, in which both eardrums had been ruptured.

At that time in the Pacific, they had some of the new sulfa powders.

Penicillin itself was fairly new at the time. They used a combination

treatment of blowing that powder in and using a little knife at the end

of a long rod to keep scraping the scab off. They saved my hearing.

The chest problem was one where nothing much could be done. The muscles

had been torn, but they decided to just let them heal back as best as they

could and of course they did. I had pain for years afterward, but

it eventually went away.

So then…back

to the hospital in New Hebrides. The living was really great compared

to what it had been before. We got three meals a day and while I

was hurt, I was able to walk around and the island was pretty.

We weren’t allowed off the hospital grounds, but you could see the little

town with its red roofs.

Efate,

New Hebrides

“All in

all, a pretty place to be.”

We did have

a lot of very badly wounded people, of course. So since I could walk

around, one of the things I was able to do was to help the corpsman with

the variety of odds and ends. A couple of times while I was there,

the influx of wounded people became very heavy and this was when ships

were sunk. Particularly, I believe, it was (USS) Atlanta, when

so many men were so badly burned. All this black, peeling skin with

guys coming in with almost no hope of living. The burn techniques

at that time were certainly nothing like what they are today. How

many of those guys are still around, all scarred, or how many didn’t live,

I really don’t know.

|

|

I did have

the one experience there that I have talked about before when right after

one of the ships were sunk, there were also a lot of Marines who came in

who had been ambushed on Guadalcanal. One of the guys, a squad leader,

had been hit by both a 50 caliber and 25 caliber machine guns. He

had some fifty holes in him from his toes right up to his head, including

one ear, which had been cut off. He had bullet holes in his throat,

arms, shoulders, stomach, and legs. They asked us to take turns,

those of us who were up and around, watching him until he died, giving

him water or whatever he wanted. One of the real miracles of the

war was that I was eventually to see that guy hopping around and crippled,

use of one arm and one leg, but was going back to New Jersey and presumably

might still be alive. Impossible, but yet something we saw so often.

You see all the television programs where someone goes “pow” and shoots

at another guy and he falls down dead. A lot of guys got shot and

shot and shot and shot, and just simply didn’t fall down dead. So

whatever it is…..some people had more to keep them going than others.

I was eventually

to move to Efate to New Caledonia, which was another place I had never

heard of before. They took us on what was called an R4D, or DC3 airplane,

which had no seats or anything. We got in the plane and sat on the

metal deck. There were five or six of us along with bags of a variety

of things that were going down to New Caledonia. Along with the luggage

or whatever you want to call it, we figured out a place to sit in between

boxes and bags. The plane was evidently somewhat overloaded because

when we took off from the airfield at Efate, suddenly the pilot was screaming

“Run forward! Run forward! Run forward!”. So we all got up

and went to the front of the plane. He couldn’t get the tail off

of the ground, and as it happened, we eventually ended up at the end of

the runway below the treetops and went between the coconut trees, which

they had cut off. I suppose we cleared the trees by maybe 10 ft.

or so. That was my first airplane ride. Then I suppose about

500 ft. over the water. They weren’t about to go very high because

the Japanese were not all that far away and they were afraid that someone

would pick them up on radar, although no one knew whether the Japanese

had radar or not.

When we

got to the edge of New Caledonia, which is a mountainous country like most

of those islands, we went bounding over the top of the mountains till we

got to this airfield at Noumea. We were put into what was called

a “Rehabilitation Camp”. In short order, we found out that what you

mostly did in a “Rehabilitation Camp” was to go someplace and load ships.

So we got back into that routine again although we would just be taken

in the morning and work kind of a normal day, and come back to the camp

at 5:00 or 6:00 in the evening. We weren’t really allowed to go into

the town, although on our way to the ships we drove through Noumea.

It was a free French town and very pretty.

The

harbor was a tremendous place. The one thing I remember most about

that stay in Noumea was the fact that we were there over New Year’s Eve.

I can remember mostly that I ended up under my bunk at midnight because

everybody else was outside shooting things off. It didn’t take anything

but the very first rifle shot and I had automatically gotten under the

bunk. So, I can remember that New Year’s Eve pretty well.

From New

Caledonia I was to go on to New Zealand. That trip took place in

February, I believe, and we ended up at a state fairgrounds, or local fairgrounds.

It was a pretty big place with horse barns and everything and we stayed

in the horse barns. The interesting part of that was that there were

fourteen of us, all who had been wounded or hurt in the service and were

back there to wait until the Third Defense Battalion came back from Guadalcanal.

They had stayed that whole time up there; what was left of them.

After the first or second day there, we started to get food for the battalion.

I mean, beer….enough for 760 men. Ice cream….enough for 760 men.

A variety of other things, but those two stand out because I was to be

pressed into service helping one of the guys doing the cooking and instead

of water, we used beer. We didn’t have easy access to water, so what

the heck. We used beer every place it called for liquid. We

were eventually to take the big ice cream cans, which held I don’t know

how many gallons of ice cream, into town and give them away. Since

I was not married at that time, that was a nice way to go and meet ladies

in town who were very happy to get enough ice cream for their family for

maybe a year in one of those cans.

The people

in New Zealand were absolutely terrific. There were hardly any young

men left because their men had gone to Tripoli, Africa, Crete, or Greece.

There was nobody but old men and the women and kids. The people felt

at that stage that we had more or less saved them from the Japanese so

that we were pretty much the fair-haired boys and almost anything that

we would want was there to have. We had no transportation, although

we were able to bum some bikes finally, and use those to drive into town.

It was not at all unusual to strap this can of ice cream on the back of

the bicycle, and have it bouncing off the rear wheel of the bike while

you went tooling into town with the ice cream starting to melt before you

got there because you had no way to pack it. This was really just

a place to wait.

New Zealand

“A very

pretty country.”

Eventually

the rest of the outfit did come. When it arrived in New Zealand,

instead of the 760 or so who had started out at Guadalcanal, there were

a little bit over 300 of them. Most of the other guys really had

not been hurt or anything, but there was a great deal of malaria.

I had malaria while I was on Guadalcanal, but not badly. Most of

the other guys had fallen sick or had nervous breakdowns or whatever.

There weren’t too many of them killed or really severely hurt, but that

is all that were able bodied after those months. You have to keep

in mind that we were already sick and rundown with malaria and all the

rest of it when I left in October. They stayed through February,

so I can’t imagine how miserable life must have been for that long a period

of time.

One of

the things I missed mentioning was that while we were on Guadalcanal we

had a fairly major earthquake. It was bad enough to upset my bunk

and dump me out on the floor. Our course, we had no idea where the

thing had been centralized. Since we had no real structures of any

kind, it didn’t do any real damage there. When I got to New Zealand

though, I was to find that New Zealand had been very badly hit. The

major part of Wellington, where we first went, had buildings all crumpled

in the street and they had a great deal of damage. It was never publicized

then, and to the best of my knowledge, I’ve never seen anything in a book

or magazine about it since.

Earthquake

Damage in New Zealand 1943

“I was

to find out that New Zealand was very badly hit.”

Earthquake Damage in New Zealand 1943

I

can remember the Red Cross hotel, and that there was a movie just down

the street. We went to the movie one day and I was sitting up in

the balcony when there was another earthquake. It was a mild one, but I

swear that balcony went all the way up to the stage and back. I couldn’t

have been more scared. Nothing broke. Nothing happened.

It just seemed as though the whole building had moved and then come back.

We were to find the next day when we were going north in New Zealand that

the little bridge across the stream on the road had moved about 6 feet

from alignment with the road. You drive down the road and come to

an open space where you had to zig across the grass 6 or 7 feet to get

on the bridge.

New Zealand

is a very pretty country. Because we had very little to do (just sitting

around waiting for the rest of our guys to join us), I was able to take

some train rides from Masterton, where we had ended up, back down to Wellington

to do some sightseeing. The harbor at Wellington is surrounded by

very high hills and you can ride up into those hills and look out over

the harbor and it’s a very pretty kind of circular view and great to look

at. The mountains between there and Masterton I suppose are probably

just really high hills but very scenic. This little train goes chugging

up the way and when it gets to the top, or at least on the trip I was on

once, they stop and pull over on a siding and you have tea or a light lunch.

Then you get back on the train and go down the other side of the mountain.

Of course, there are a lot of sheep and very pretty grass with little lakes.

It is an extremely nice country.

North of

Masterton, toward the extreme northern end of the island, are some hot

springs of a kind of molten lava coming out of the earth. Hot steam

coming out, really smelly stuff. I suppose (it) is a great deal like Yellowstone

although I have never been there. This place was and still is a big

tourist attraction, and we did get up that far to see what that part of

New Zealand was like. Basically, good food and stuff. We used

to be able to go to a restaurant for instance, and have steak and eggs

for breakfast for a shilling, which at that time was worth about 22 cents

in American money. So food certainly was no problem, particularly

since everybody was battling all these older people and each other to see

how many Marines they could invite into their homes and feed. While

I didn’t drink at the time, we did make a trip to what was called the “Slight

Grog” dealer or a bootlegger. Since the town of Masterton was a dry

town, this bootlegger set himself up right outside the fence to the fairgrounds

and so all we had to do was climb over the fence to get there. I

had my one and only drink of scotch that I have ever had in my life there.

The two guys I went with bought this bottle of scotch and I had a drink

of course since that was the thing to do. I suppose that bottle of

scotch was maybe 80 or 85 degrees. Now I suppose that scotch if it

is cold maybe doesn’t have a very bad taste, but it was like drinking cod

liver oil to drink that hot stuff. So that kind of deterred me from

doing any great amount of drinking during that period of my life.

Eventually

the outfit was allowed to send some men back to the States. I was

one of those fortunate few to get a chance to come back home.

The trip

back home from New Zealand turned out to be very uneventful, although a

very long, long trip. We did have one stop at Pearl Harbor and Honolulu

again in which they took on some supplies and extra troops that were going

back to the United States from Pearl Harbor, mostly Navy people.

We came

back to the United States under the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco,

where incindentaly we had departed on our original trip out. We went

from there back to San Diego and Camp Elliot, a regular Marine base for

processing. We were to stay in quarantine for 3 days and not be allowed

to go on liberty or anything. As soon as I arrived there, I had somehow

gotten in touch with my friend Bernard Young and he and I went into town

together. He was by then a Lieutenant. He got me a pass and

we got off the base and went into San Diego and had a very pleasant number

of days doing that before we were done with all of our health tests and

allowed to go home on a 30 day furlough. I had not at that point

had any time off in the Marine Corps because I had been moving all the

time.

I was so

anxious to get home, but the trains took four days to get to Ohio.

So….I came

back to Ohio for a 30-day furlough.

E-Mail: WBaird721@aol.com

Oral History of Service Volume II

(click to enter)

(Return to Main Page)

Please take the time to share your thoughts

by signing my Guestbook

| Sign |